Lesson Outline

When terrorists struck Paris on Nov. 13, 2015, taking 130 lives, news consumers following the story through Internet postings saw the power of social media at its best and its worst.

A key News Literacy lesson teaches us that in the digital age, news consumers are also news producers who can choose to post information, images and videos responsibly. Or not.

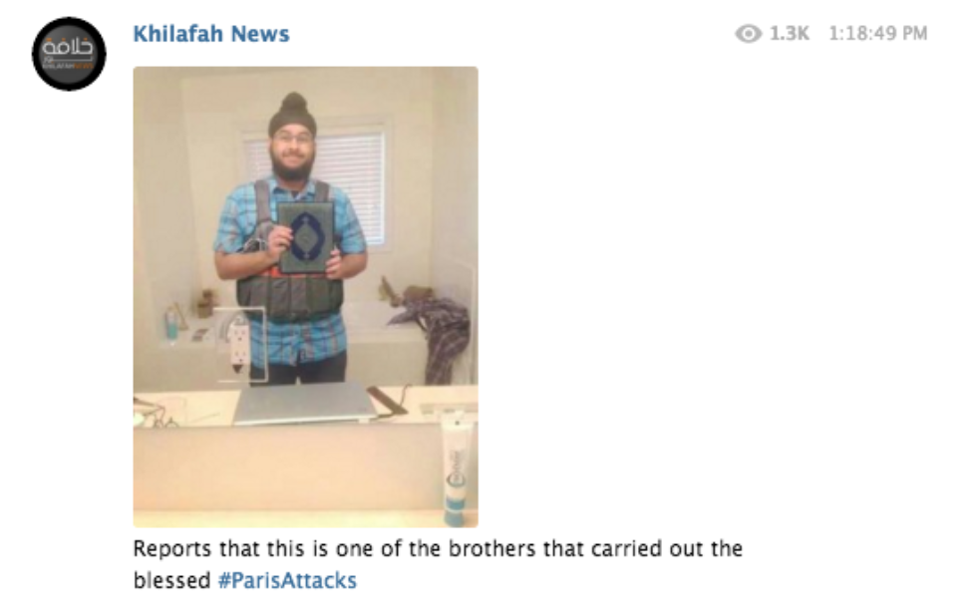

Take, for example, the case of the case of Veerender Jubbal, whose photo wound up on the front page of a Spanish newspaper as a possible suspect. That was after his image began to circulate on social media holding a Koran and wearing a suicide bomber vest. It was even shared by one of the pro-ISIS channels on Telegram, the app that the extremist group used to take responsibility for the attacks in Paris.

But Veerender Jubbal had nothing to do with the attacks. He was the victim of a sick prank that involved manipulating a photo he’d taken of himself.

News has the power to alert, divert and connect us, and nothing connects us the way tragic breaking news does. Television made the world feel smaller by turning us into what Marshall McLuhan called “the global village,” with news stories like the assassination of President John F. Kennedy or, more recently, the World Trade Center attacks powerfully connecting news consumers. Social media made that connection interactive, and the reaction to the Paris attacks demonstrated the positive and negative implications of that.

Some posted images of the Eiffel Tower shrouded in darkness after the attacks. Others shared a poignant cartoon they said had been drawn by the world-renowned street artist Banksy.

What they may not have known was that the tower goes dark at 1 a.m. every morning. Or that @therealbanksy is a “fan account” that routinely posts artwork by others. (In this case, it was by French graphic designer Jean Jullien.)

The problem, wrote Katie Rogers of the New York Times, is that there is a dark side to that interactivity. “What happened in Paris,” she wrote, “fits into a pattern of behavior that seems to emerge every time a catastrophe strikes in real time: People will share anything online in order to share something online.”

The power of social media and crowdsourcing has a positive, self-correcting side as well, one that also could be seen after the Paris attacks.

The photo manipulation that portrayed Sikh gamer Veerender Jubbal as a Muslim terrorist was exposed by Grasswire, a site that uses crowdsourcing to curate social media posts in real time. Its members are dedicated to exposing posts relating misinformation and sharing trustworthy reports.

“They even PhotoShopped his eyebrows so he would look angry ...” said Joanne Stocker, Grasswire’s managing editor, who was interviewed on NPR’s “On the Media” the following weekend.

She told co-host Brooke Gladstone the retweets of the faked photo were not surprising. “If you’re in the heat of the moment and you see this come across, and it’s, ‘Oh my God, you know, this guy’s one of the attackers!’ People don’t actually stop and look at it with a critical eye, for the most part. They just reflexively hit retreet.”

In the aftermath of an event like the Paris attacks, Stocker said, the key for people on social media is to be patient. The immediate reports are going to be "messy," she said. “Governments are going to get it wrong, the media is going to get it wrong and witnesses are going to get it wrong, and it doesn’t mean that it’s a conspiracy. It just means that it’s breaking news.”

Her advice echoes a key News Literacy lesson: In cases of provisional truth, follow the story as the facts come in and truth begins to emerge.

QUESTIONS FOR THE CLASSROOM

- Would you have retweeted any of the Paris attack tweets pictured in this news lesson?

- Can you think of a News Literacy lesson or concept that would have helped you decide whether to believe or share any of these tweets?

- Have social media posts ever helped you better understand the facts in a breaking news situation?

-

Key Concepts

-

Course Sections

-

Grade Level

-

0 comments

-

2 saves

-

Share