Lesson Outline

“When we’re looking at disasters," says journalist Jonathan Katz, "especially ones that happen in other parts of the world, I think the most important thing that we can do as journalists is to communicate that it’s not about us.”

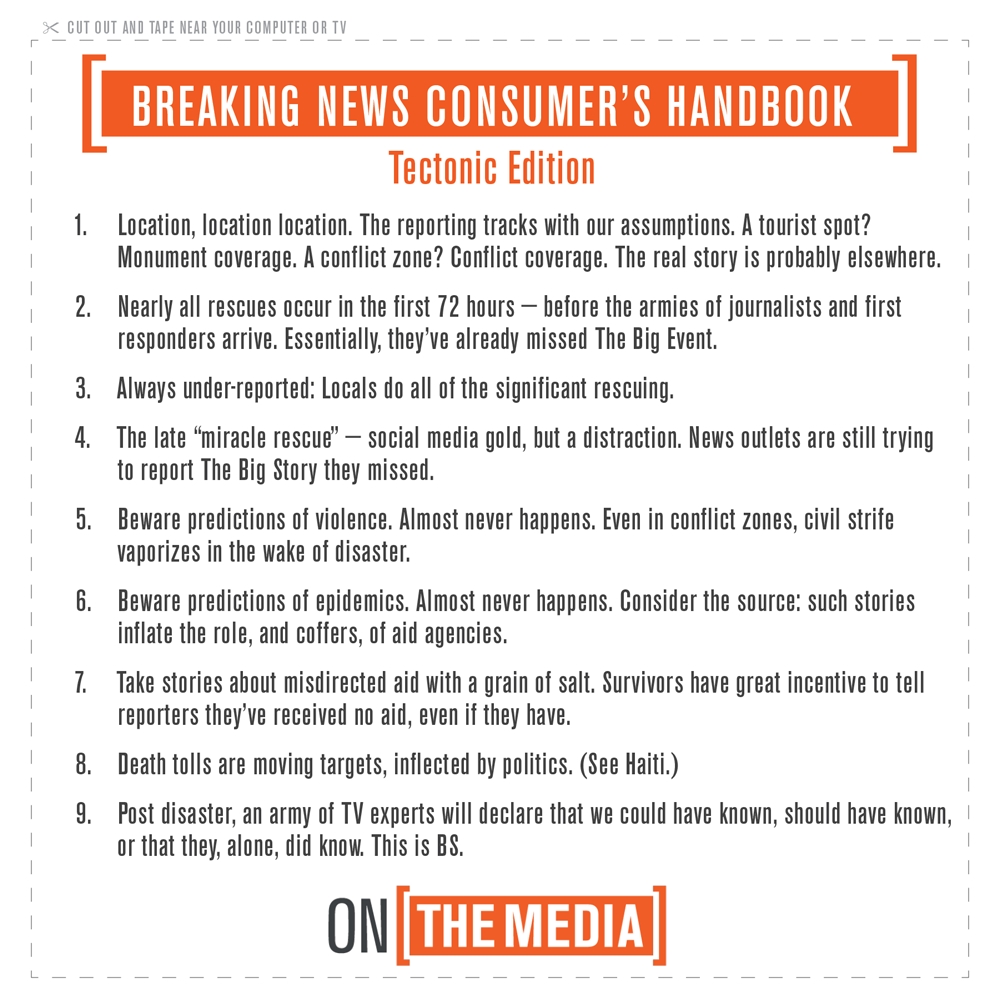

Katz, who covered the 2010 quake in Haiti for The Associated Press and wrote a New York Times article headlined, "How Not to Report on an Earthquake," was interviewed recently on NPR's "On the Media." His observations contributed to the latest installment of the show's "Breaking News Consumer's Handbook." Rule 3 in the "Tectonic Edition" of the handbook says: "Always underreported: Locals do all of the significant rescuing."

That shouldn't come as a surprise, especially in remote areas that take time for international rescue teams and journalists to reach. Still, Katz observed from his own experiences and from coverage of 2015's Nepal quake, most of the attention goes to the international search and rescue response.

Why? You can attribute some of that to a notion that these news reports have reinforced over time -- that the international rescue and relief teams are the best sources of information and the real experts on the scene. News outlets also have a natural bias to toward reporting the local angle, which in these cases tend to be the audience's representatives on the scene. (That's the same reason U.S. networks covering the Olympic Games focus the most coverage on how American athletes are doing.)

Inflating the role of outsiders in the aftermath of an earthquake not only gives news consumers a distorted view of what's happening in places like Nepal, it can have a practical impact that hurts the recovery effort. “When the earthquake struck in Haiti, the American Red Cross raised $486 million,” Katz said. “They had four people in Haiti at the time of the earthquake.”

Speaking with WNYC's Brooke Gladstone, Katz also told "On the Media" about the tendency for news outlets to focus on predicatable and often-unfounded disaster narratives. “You expect for there to be violence. You expect for there to be unrest," Katz said. "And you don’t want to miss this story, and your editor certainly doesn’t want you to miss this story. And, frankly, viewers expect this story, too.” So you ask people questions and, inevitably, he says, “a hammer finds a nail.” The result, though, is that “we’re focusing on the wrong things and asking the wrong questions,” Katz said.

And when that happens, Katz said, news consumers don't hear enough about the “very real drama of survival.”

Questions for Classroom Discussion

1. What is the practical impact of over-reporting the role of international relief and rescue workers in the aftermath of an earthquake?

2. What are the most important takeaways for news consumers from the latest "Breaking News Consumers' Handbook" offered by NPR's "On the Media"?

3. When reporters expect a certain outcome and pursue information that would support those conclusions, is a type of cognitive dissonance or confirmation bias at work?

4. As a news consumer, what kinds of post-earthquake stories would you look at skeptically?

Additional Resources

Did you miss the original "Breaking News Consumers' Handbook" and the "Infectious Disease" edition created by "On the Media"?

-

Key Concepts

-

Course Sections

-

Grade Level

-

0 comments

-

0 saves

-

Share