Lesson Outline

SERIES: Making sense of the campaign / Lessons in News Literacy. Drawing upon the 2016 presidential campaign for examples, this series of teacher's guides provides everything instructors will need to tailor foundational News Literacy lessons to their students and classroom. You'll find a detailed briefing identifying and applying specific News Literacy concepts, clear objectives and takeaways, multimedia, discussion questions and assignments that can be used in the classroom or as homework. We're also providing a PowerPoint presentation for classroom use that you can use or modify. We're also providing a PowerPoint presentation for classroom use that you can use or modify. As the campaign unfolds, we will supplement this guide with timely examples.

TOPIC: How can news consumers following the presidential campaign on TV distinguish between straight news, opinion journalism and partisan assertions and speculation?

CONCEPT: Understanding the labels and language that can be used to tell news reporting and opinion journalism apart and how the attributes of journalism (verification, independence and accountability) distinguish opinion journalism from partisan assertion.

OBJECTIVE: This lesson will teach students what to look and listen for in their search for reliable information about the candidates and their campaigns on TV, where the line between news and opinion is often blurred. They will learn about the labels and language they can be used to separate news anchors and reporters from opinion journalists and from the political experts and operatives that networks invite to offer their perspectives. This will allow them not only to distinguish between news and opinion, but also to determine which information they can rely on because it carries the three key attributes of journalism — verification, independence and accountability.

Download this lesson as a Powerpoint presentation to use in your classroom.

Download this lesson as a Powerpoint presentation to use in your classroom.

Campaign news or opinion?

Looking straight into the camera, MSNBC’s Mika Brzezinski delivers the latest news from the 2016 presidential campaign, reporting on a Monmouth University poll and a Politico story about Bernie Sanders being discussed as a potential vice presidential nominee for Hillary Clinton.

Then without missing a beat, the “Morning Joe” co-host turns to senior political analyst Mark Halperin and says, “You know, I don’t think she would do that. Does anybody?”

Was Mika Brzezinski delivering the news or opinion? The answer, of course, is both, and that’s why the moment captured in this video clip, where Brzezinski seamlessly moved from anchor to commentator, is emblematic of one of the key challenges facing news consumers trying to make sense of the 2016 presidential campaign. TV news — and cable news shows like “Morning Joe” in particular — routinely blurs the line between news and opinion. The challenge for news consumers is to recognize the difference.

While younger news consumers are turning to the Internet for news, television remains the primary news source for most Americans, according to the Pew Research Center. So it should come as no surprise that cable news outlets were named “the most helpful election source” in a recent Pew survey.

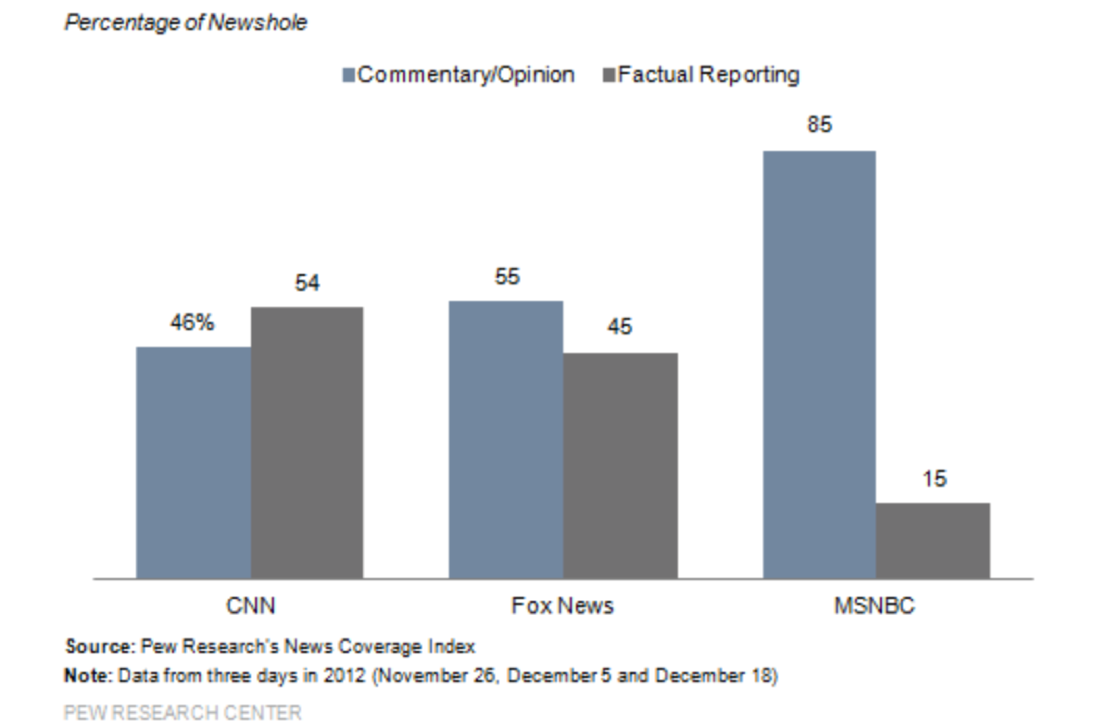

Cable news outlets do devote more time to campaign news than ABC, NBC or CBS, but the economics of filling a 24/7 news hole long ago made opinion-driven programming a mainstay for MSNBC, Fox News and CNN. Programs that rely on commentary are relatively cheap to produce and deliver ratings. While MSNBC has recently scaled back some of its commentary lineup in favor of more traditional news shows, a 2012 Pew study found it was devoting 85 percent of its airtime to commentary and opinion.

So how can we tell if the information we’re getting is news or opinion on TV during this election season?

1. Look who's talking

Most newspapers and many websites clearly label opinion — editorials, where news organizations make political endorsements and take official positions, columns and opinion pieces by partisans. That kind of labeling is less clear and easier to miss on television, but it’s an important tool for news consumers trying to separate news from opinion.

These labels — generally, name and title — briefly appear on screen when a speaker is introduced and sometimes are flashed again. The show’s anchor sometimes provide additional details about their qualifications or allegiances during the introduction. A key challenge for news consumers is distinguishing network journalists from outsiders who may have some expertise and insight but lack independence.

Here are some of the labels to look and listen for:

Anchor. Generally the host of the show or newscast. In a straight news program, the anchor will generally avoid offering opinions.

Correspondent. These are reporters. Like the anchors, when they’re on the air, they report news that’s been through the journalistic process of verification. When their reports include opinions, they belong to the people being interviewed. That’s just good reporting. Sometimes, titles like chief correspondent or bureau chief are used for these journalists.

Commentator. This is an opinion journalist — the equivalent of a columnist in the TV news world. It’s the commentator’s job to take sides, offering fact-based opinion that is subject to the verification process. Opinion journalists may share the perspectives of political parties and politicians, but if they are following the standards of the Society of Professional Journalists, they maintain their independence by remaining "free of associations and activities that may compromise integrity or damage credibility."

Here’s an audio clip of Cokie Roberts explaining the difference between a journalist and a commentator and why she, as a commentator for NPR, could write a syndicated column calling on Republicans to stop Donald Trump.

Analyst or Contributor. Here’s where the line begins to blur. An analyst offers information and insight, but unlike an anchor or correspondent, this title is sometimes used for experts who are not journalists and may not be independent. (Sarah Palin, for example, is a former Fox News contributor.) They are paid to offer informed opinions, conjecture and speculation based on their expertise.

Consultant, Pollster, Strategist. They may be informed or experts in their own right, but they are not journalists. They are political operatives who may blatantly disregard fact-based evidence and use emotion to reach a predetermined conclusion and play to a specific audience. Networks routinely invite current or former political operatives to share their opinions, and they’re often identified as either a Democratic or Republican strategist.

In spite of these labels, the problem for news consumers is that a speaker’s allegiances aren’t always clear to the audience before he or she begins talking.

Take a look at this clip from NBC’s Meet the Press on Jan. 17 of Stephanie Cutter, who was introduced as a former campaign official for President Barack Obama.

What you don’t know as a viewer is that the consulting firm she co-founded has been hired by the Clinton campaign and paid at least $120,000 since last June, according to The Intercept. Teachers may wish to use the first assignment below in class to reinforce this lesson.

2. Listen to how they're talking

Another way for news consumers to determine if people are reporting the news or giving an opinion is to listen closely not only to what they’re saying, but how they’re saying it. First-person statements are a reliable indication that someone is giving an opinion.

When MSNBC’s Mika Brzezinski shifted from news to commentary, she began speaking in the first-person (“I don’t think she would do that.”). There was no labeling — the language she was using was really the only warning news consumers had.

Exaggeration, emotionally loaded words and sarcasm are also opinion neighborhood markers.

Let’s take a look at a riveting piece of television on CNN on Super Tuesday. Make a note of first-person declarations and the use of exaggeration, emotionally charged language or sarcastic tone as you watch.

Anderson Cooper, whose title is CNN anchor, is reporting that Rubio is leading in Minnesota as the clip starts. SE Cupps, who is listed as a “political commentator” at CNN, leads off the discussion with the charge that Donald Trump tries to “otherize” people, to which Jeffrey Lord, a Trump supporter and former Reagan aide, replies sarcastically, ”That’s liberal speak.” Lord continues to say the Republican establishment’s view of civil rights is to tip the black waiter $5 at the country club, a ridiculous contention that has no basis in fact. (34:11) Van Jones, another CNN political commentator, jumps in and an argument ensues about Donald Trump’s disavowal of the KKK. Both Lord and Jones are using emotionally loaded words and the first person to present their views. (See transcript of this clip under resources.)

3. Is it opinion journalism — or just opinion?

Opinion journalism has been around since Colonial times and is meant not only to inform but to sway public opinion. Savvy news consumers turn to straight news reports to become informed and then turn to opinion journalism for insight and understanding. Both are based on the principles that distinguish journalism from all other media: verification, independence and accountability.

By definition, opinion journalism is one-sided, but it always draws conclusions from a fact-based inquiry with an allegiance to the truth. Opinion journalists, typically the most experienced and elite reporters, use evidence and persuasion to make their case. They marshal the facts to promote a particular point of view.

Here's an example of legitimate opinion journalism from MSNBC's “The Rachel Maddow Show.” Though the host's political leanings are no secret, she makes her case with facts subject to the journalistic process of verification. She is independent and accountable for her work.

Sometimes it’s not that easy to separate legitimate opinion journalists from political operatives who make unsubstantiated assertions. Take a look at this clip from Fox News on whether Hillary Clinton will be interviewed or indicted by the FBI. Is this legitimate opinion journalism based on verified information or mere assertion and punditry playing to a conservative Fox News audience?

Everyone in this clip is labeled: Bret Baier is a Fox News anchor; Judge Andrew Napolitano is a Fox News senior judicial analyst, Charles Lane, Washington Post and Fox News contributor; Charles Krauthammer, syndicated columnist and Fox News contributor. All but anchor Bret Baier offer their opinion in the first person, and everything the panel says on whether Hillary Clinton will be interviewed and indicted by the FBI is pure speculation and assertion.

So the challenge for news consumers is not only to separate news from opinion, but also opinion based on facts from pure conjecture and unsubstantiated or spurious assertions. As this quote attributed to Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan says: “Everyone is entitled to his own opinions, but not his own facts.”

THE TAKEAWAY

1. The best way to tell the difference between news and opinion is to listen critically to what is said and look for labels.

2. Labels don’t always tell the full story about a person’s background or current ties.

3. Language and tone can also indicate that what you’re hearing is opinion, not news.

4. All opinions are not created equal. Opinion journalists base their arguments on a fact-based inquiry while pundits make assertions and disregard facts to reach a predetermined conclusion.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Most news organizations forbid its journalists from taking public positions on political affairs. If they do, they risk losing their jobs, as NPR’s Juan Williams did when he made comments on Muslims on Fox News. Do you agree with this policy or do you think it needs to be relaxed?

2. Critics of pundits like FiveThirtyEight’s founder Nate Silver say that political pundits are useless and make predictions with no evidence. Is there a place for pundits in the 2016 election coverage? What’s their value?

ASSIGNMENTS

Example 1: Watch this clip of CNN Contributor Maria Cardona. Does her title of "Democratic Strategist" give you enough information about her background and allegiances?

According to The Intercept, in 40 out of 50 appearances on CNN, Maria Cardon was described a as a Democratic Strategist or CNN contributorwith no mention of her ties to the Clinton campaign. She is a super delegate who has already pledged support for Clinton, and her lobbying firm has helped the Clinton campaign with fundraising. Since The Intercept story was published, CNN has been introducing her accurately.

Example 2: Watch this clip from Fox News on whether the Republicans are heading into a contested convention and make a note of who is offering facts to support their position and who is simply stating views that affirm the audience’s beliefs.

Judge Andrew Napolitano, a Fox News senior judicial analyst, says the party is going in two ways and says he can’t predict what will happen. Mara Liasson is a news reporter for NPR but in this case, she is labeled “NPR and Fox News Contributor.” She clearly offers her opinion, which she does not do in her NPR reports. It could be easy to miss that she has put on her commentator hat though since she is first identified as a member of National Public Radio. In this clip, she speculates that this is the dissolution or utter transformation of the Republican Party. She believes there will be a contested convention. Bret Baier then reports on an exit poll that shows about 40 percent of GOP voters would consider a third-party candidate if it’s Trump vs. Clinton in November. Fox News contributor and syndicated columnist Charles Krauthammer says the third party candidate is a pipe dream. With the exception of Bret Baier, these guests are just offering their opinions. Their commentary is pure assertion and punditry.

RESOURCES

Videos

- https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6mgAy5NdTA3LU5BblEzSmlTcUE/view

- https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6mgAy5NdTA3c0Z1M0JUY0F5aFU/view

- https://theintercept.com/2016/02/25/tv-pundits-praise-hillary-clinton-on...

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ze7mWCiwfgk

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FLVf88WFrdQ

- http://video.foxnews.com/v/4825563042001/does-hillary-have-a-date-with-t...

- http://video.foxnews.com/v/4806287043001/gop-preparing-for-contested-con...

Audio

Articles

- http://www.stateofthemedia.org/2013/special-reports-landing-page/the-cha...

- https://theintercept.com/2016/02/25/tv-pundits-praise-hillary-clinton-on...

- http://www.journalism.org/2016/02/04/the-2016-presidential-campaign-a-ne...

- http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/02/26/msnbc-shakes-up-programm...

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2016/03/02/what-cnn-analy...

- http://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp

Looking for a previous lesson? Check out our ARCHIVE of Presidental Election Lessons

-

Key Concepts

-

Course Sections

-

Grade Level

-

0 comments

-

1 save

-

Share